David and Ruben Firnenburg are some of the most promising young guns around, being among the five youngest people ever to redpoint 9a.

David and Ruben Firnenburg are some of the most promising young guns around, being among the five youngest people ever to redpoint 9a.

Born respectively in 1995 and 1997, they made the headlines multiple times last winter, as they sent a number of hard routes in Catalunya.

However, hard sends are not the only thing that makes them special. Despite their young age, they have very interesting opinions and a great awareness regarding important topics such as perceived grades, long-term projecting and access issues…

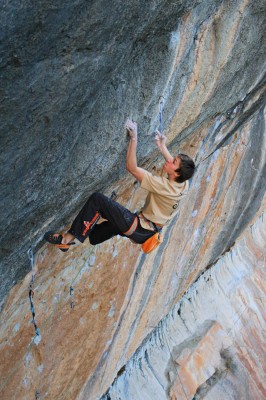

Photo: David and Ruben Firnenburg © Firnenburg Archive

First, a customary question about the beginning of your climbing life: when, where and how did you start?

David & Ruben: already at a young age we were enthusiastic and curious about being active and outdoors. Our family would typically stay in the Italian and Swiss Alps for outdoor activities during the holidays. While hiking and mountaineering, our father noticed that we were very interested in climbing any small boulders we could find on the way.

So one day he suggested that we tried an easy route in the climbing garden of Maccagno at the water’s edge of the big Italian lake called Lago Maggiore. From the very beginning he was always supporting us in what we wanted to do, took care of us, showed us new things and was guiding us. Looking back, these were very thrilling and adventurous experiences for us as small kids, we felt free and it was always funny and challenging.

When and how did you decide that climbing would be such an important part of your lives? Was it a realisation tied to a specific result or send, or a longer process?

David & Ruben: Right from the start, climbing and being outdoors were extremely fascinating for us. We enjoyed the diversity and freedom which given by travelling to various locations, discovering new landscapes and rocks, working on demanding moves, testing out our limits on physical and mental challenges, meeting different people, forming new friendships, learning new languages, etc. There are always new things in climbing you haven’t seen before and that you want to try out.

This last winter, up to January, you have been the two guys climbing the hardest in Spain, with sends up to 9a. Could you tell us more about the whole trip, starting from Margalef, the first crag you guys visited?

David & Ruben: David arrived in Catalonia in late November, after having spent two weeks bouldering in Fontainebleau, with our climbing friend Lena Herrmann. He began in Margalef and was staying in a van. Ruben flew down on the 20th of December. On the 27th of December we moved to an apartment in Cornudella de Montsant near Siurana. There we stayed with friends from France such as Solene Amoros and Ruben’s girlfriend Camille Masseran, plus friends from Norway such as Jakob Heber Norum and Thilo Schröter. We stayed together until the 4th of January. After that we went home, except for David who continued to stay in Siurana, primarily with Daniel Jung, until the end of January.

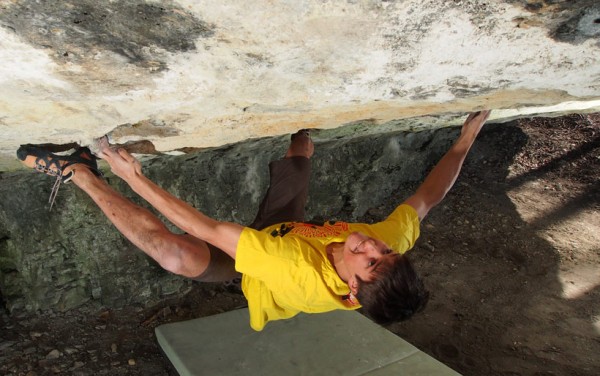

Ruben trying A Muerte, suitably dressed in colours matching the black and orange streaks of Can Piqui Pugui, Siurana © Firnenburg Archive

Ruben, you managed to send Era Vella, a very popular and highly rated 9a, which was your first line of that grade. When we met in Kranj, you told me about how you had been trying the line before, skipped a quickdraw high up while going for a good redpoint attempt, fell a long way and broke your wrist : ( Would you like to tell us more about this big project?

We often read about hard redpoints, but they rarely involve traumatic injuries of this type. What were your feelings in the months leading up to this winter with regard to Era Vella? Were you nervous about going back to the “crime scene”?

Ruben: I started trying “Era Vella” in the winter of 2012. But at that time I was also figuring out which 9a I wanted to try first as I had started to work also on “A Muerte” in Siurana, where I also had a look at “Estado Critico”. I finally chose Era Vella because the conditions were better in Margalef at the time and I liked the style of the route. Unfortunately the time wasn’t enough and I had to return for another trip. I took three days off school around Easter 2013, thus extending my holidays with the hope of sending the route. As I came really close on my 16th birthday, being absolutely sure to send it within my next go, I took an unneeded risk by skipping quickdraws to save up some stamina, but I had a big fall from the top of the route and broke my wrist.

I knew that no proper climbing was going to happen in the next couple of months and I had to endure the most frustrating and disappointing time in my climbing career.

I had no chance of coming back to Era Vella because the competition season had already started. When I had the possibility to come back last winter I was maybe a bit scared but also really motivated and maybe sort of determined because I really wanted to finish the route. During the last trip it took me 4 days of work and after 2 days of rest I finally clipped the anchor on my first try that day. I was really happy and glad that I’d finished this mental challenge!

What about the actual send? Tell us about that special day…

Ruben: The day I sent Era Vella was actually a normal climbing day, but my expectations were high and I knew I could do it if I were to stay focused. I am sure my girlfriend Camille gave me some extra energy because it was the first time she belayed me on that route and I could send it directly on my first go. When I was lowered down to the ground it was a very emotional moment for me and the feeling of having sent a route you’ve tried so hard for a long time is beyond words. I spent the rest of the day climbing some easy stuff and belayed Camille.

David, as the older (and overage!) brother, as well as somebody who has climbed Era Vella before, what advice and guidance did you offer to Ruben during his big project?

David: For me it was and still is very important to support my brother whenever I can. After my ascent of “Era Vella” in 2011, we were discussing and thinking about feasible projects for Ruben in Catalonia. I told him that “Era Vella” is definitely a route not to be missed because it fits his style very well and above all it is a very impressive line with interesting climbing features. During spring 2013, Ruben drove down to Catalonia with our dad to start working on the route, but I couldn’t be there because I had to study for my final high school exams. He found out his own beta to solve the crux moves and there was basically no need to discuss the route further. As he recovered from his injury, I visited him in Zurich (he was there for his exchange year) and we had some nice climbing days together in Ticino. I think that it was very good for Ruben to be mentally engaged in something else and we didn’t talk that much about the project. After the World Youth Championships in Canada in August he was back in Germany and had to settle in a new school. He started training for the project again and was totally focused and motivated to take it down during the winter holidays. At that point I did my part belaying him in the route and giving him mental advice. He had to struggle not to give up and to perform better and better. Sometimes I had to remind him of how to talk himself into a positive frame of mind. Everything else he managed autonomously and I didn’t have the feeling that he needed my help anymore. In the end I think it had a lot to do with feelings, because his girlfriend was belaying him on the day he sent the route ; )

Then it was time to go to Siurana, where David went on a rampage and climbed the famous Estado Critico (now 9a) and a number of 8c+ routes. We’d love to hear all the details!

David: The highlight of the trip was definitely Estado Critico for me. I wanted to climb a 9a this winter and after the onsight ascent of my good friend Alex Megos I was very excited to try the route too. When I checked out the first crux (a long move from bad sideholds into a good crimp) it felt very hard for me and I decided to climb some easier routes, if anything because I had to build up more endurance to be able to climb longer routes like Estado Critico. That’s why I’ve been working on several 8c+s before.

“L’Odi Social” was the first one. It’s a pretty technical, slightly overhanging route on small crimps. I could send it in just 8 tries. But afterwards I didn’t feel fit enough to try Estado Critico yet. I went on with “Politicamente Corruptos”, a very steep, powerful and long climb in Margalef, while Ruben was trying Era Vella. After climbing it with relative ease on a windy day, I felt confident to try Estado Critico.

During New Year’s period, Siurana was heavily crowded with climbers and Estado Critico shares the same start with the very popular “Kalea Borroka” (8b). It was impossible to work intensively on it because every day there was always a long queue of climbers in front of Kalea Borroka. Instead of joining the queue and waiting all day long to have a single try, I went to the left side of El Pati and decided to try “Pati Noso”, which wasn’t crowded. It took me 4 days to finish it. It was a bit of mental battle for me because I fell two times at the last hard move after 30 meters of climbing. I had to try it over and over again and it was quite frustrating for me because two holds broke while I was very close to finishing it. But I have to say that it was good training for Estado Critico.

At the beginning of January Siurana became less busy and I could finally focus on Estado Critico. Working hard on the route, I managed to battle myself a few moves further up the wall with every try. Falling four times at the last hard boulder problem before the top gave me the confidence that the send was close. Redpoint happened on the 7th of January after three consecutive days of climbing. I was very satisfied with my performance and I still had some days left to go for another hard project.

I wanted to project the routes close to the famous La Rambla and I managed to finish “El Rastro” and the Huber classic “Broadway” before leaving Siurana on my way back to Germany. I was very close to “La Reina Mora” too. Another fantastic line there! And guess what is going to be the next one? “La Rambla”, for sure ; )

The older brother pulling hard on Hänsel ohne Gretel (8b) at the Holzgauer Wall in Frankenjura © Firnenburg Archive

It looks like it took you a longer time to climb Pati Noso (8c/+) than the 9a Estado Critico… What do you make of grades?

David: Some people claim that some routes are graded too hard or sometimes too soft. They are talking about “grade inflation” or other problems. I think that grading is ultimately a subjective evaluation. There are so many different factors that influence significantly the perceived difficulty. Factors such as weather conditions, different route characteristics or the physical build of the climbers make objective comparisons really hard, in my opinion.

I believe climbing grades are best used simply to organise climbing and training. But they are not everything. Climbing is complex. For instance, in areas like the Elbsandstein or the Peak District, grades focusing on the mere technical difficulty are not that important. The climbers are confronted with another climbing philosophy where safety and style are also part of the game. That’s why they have established other grading systems because you can’t compare this different approach with that of the French or UIAA systems. Those traditional forms of climbing simply define the challenge differently and set other standards. And that’s exactly what makes climbing complex and interesting. It’s that diversity and freedom that I really enjoy about climbing and which creates unforgettable adventures.

I’d like to ask you more about your brotherhood. It’s maybe just a coincidence, but Germany has quite a tradition with brothers: from the Schmid brothers (first to climb the north face of the Matterhorn) to the Huber, Bindhammer and Jung brothers of more recent days. Do you know (personally) any of these other famous climbers? Did you relate to them and if yes, how?

David: We are friends with some brothers like the Jung brothers from Germany, the Hamer brothers from England or the Bonzom siblings from France and we know several other climbing siblings too. With your own brother and sister you normally have the longest relationships of your life, longer than the one with your parents, partners or friends. That makes it something very particular. Especially if you (as siblings) more or less have the same age, it’s easier to do something significant together because you are in the same phase of life, having similar or even the same goals. It’s really nice to have a brother who shares the same passion and with whom you can do many things together. And that’s what we do with the other brothers too, and how we relate to them. We go climbing together, support each other and have fun. The two weeks I spent with Daniel Jung in Siurana (after Ruben went back home) were a great time.

Ruben throwing shapes as he climbs Vizija (8c) on the Slovenian limestone of Mišja Peč © Firnenburg Archive

What about the specific dynamics between the two of you? David, do you enjoy being the older one and re-seeing your progress in Ruben’s climb?

David: I suppose that Ruben is the more brave type of guy, he’s willing to take more risk. I’m more cautious and considered. The combination of the two of us is a good mix. Being the older one means that I have some advantages, but also challenges. I can be an example for Ruben regarding a lot of things. For him, it’s then often easier to choose between two decisions because he already knows what I’ve chosen before. I can give him a lot of advice and tell him my own story and experiences. Thereby he does not have to work on conflicts like I do which is also very useful. He can choose the easier way. However that’s just one of the many facets of this. We learn from each other, develop differently and go our own ways which is really important too. But climbing is something that connects us very strongly.

And Ruben, how do David’s results motivate you or maybe sometimes put you under pressure?

Ruben: I wouldn’t say that they put me under pressure. They rather give me motivation and make me try harder. But it wasn’t always like this: when I was younger I wasn’t as close to the grades David managed to climb as I am now. But we always helped each other and we are always happy if the other can climb his project.

What are your preferences for the style of route climbing or bouldering? What are the strengths you like to play to?

Ruben: I like to do both, sport climbing and bouldering, even though I have better results in climbing because I am more of an endurance type of guy. My finger strength is quite good and I am light compared to other climbers. Moreover I think I have a good body feeling and a strong will which is one of the most important things. When I do rock climbing I prefer pockets and crimps.

David: I don’t prefer bouldering or lead climbing and I like to climb pretty much everything. Crimps, overhangs, slabs, short problems and also long problems, DWS, big wall climbing (although I haven’t done much of it so far), pockets, dynamic moves, etc. When it comes to slightly overhanging climbs on crimps and pockets, I’m good at it. I like every style of climbing which is complex, challenging and adventurous.

And in the next 2-3 years, do you plan to focus more on competitions or on outdoor climbing?

Ruben: I am still young and I think it’s good to combine competition climbing with outdoor climbing. But I started climbing outdoors and for me it’s more the natural way of climbing, the one I want to continue doing for longer than competitions.

David: I will definitely focus on outdoor climbing in the future. I am not sure how long I will continue doing comps. I guess the next 2 or 3 years for sure. It depends on my own development and how it will be evaluated by my National Federation (the DAV). It is the largest mountain sports federation in the world, yet we collectively struggle with a lot of difficulties. Ruben and I did exchange years in Innsbruck and Zurich and we have good climbing friends from Slovenia and France too. In comparison Germany lacks structures and organisation. This leads to problems in the scouting of talents, their promotion and the management of their competition performance. Most clearly this can be seen in the Lead World Cup. If one was to consider the size of our country, its number of inhabitants, its economy, the number of climbers or any other statistic you may take, one can see at a glance that we are underperforming our potential. I think that without the type of organization boasted by the countries mentioned above, good results for our national team will largely be left to chance or to “heroic” achievements of individual young athletes and their families. My national boulder coach, Udo Neumann, recently got the point across in the magazine of our federation: they will have to think about what competitive climbing is worth to them if they want to see the same success other countries have.

Some people may consider these points as an excuse, but they are things we should discuss. As an example I would like to mention Russian climbers. I know about their conditioning and training through my good friend Irina Kuzmenko from Krasnojarsk. They overcome many similar difficulties through dedication and creativity. Last but not least I have to mention the excellent trainers we have in Germany such as Patrick Matros, Dicki Korb, Udo Neumann and Guido Köstermeyer.

In my opinion, the future of competition climbing in Germany will very much depend on how our climbing federation will take into account their suggestions and advices.

Personally, we receive good training hints from them. We are also very thankful to be supported by several private sponsors such as Scarpa, Beal and the Northern German Federation for Climbing and Mountaineering. Above all our family is the main supporter of our climbing activities on the rocks and in the competitions.

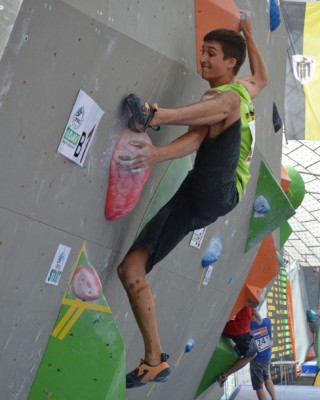

David during the 2013 Boulder WC in Munich. Between 2010 and 2012 he stepped on the podium of international youth events 8 times © bergleben.de

Can you tell us a bit more about your approach to competitions? You have had good results in both lead and boulder, so you must be doing something quite right! : )

Ruben: A good training is the basis to perform well in competitions but you also have to be mentally in shape. It’s important to trust yourself and feel right about what you do. From my point of view will is the most important thing you need because it makes you train constantly and try hard even if you get disappointed. To me, it’s the most important asset.

David: I like to use climbing to test out my limit, physically and mentally, and to exceed it. Being able to climb harder and harder motivates me. All the people I get in touch with, the nature, the travels, the rocks and everything else inspire me. I think these things are a good basis to train and work hard toward my goals in climbing. This attitude can teach me a lot also about different aspects of my life. Since I was 10 years old, I have been training for specific aims. I started to work with four-week periodisation phases for both routes and boulders. I am not very inclined to powerful movements therefore I focused a lot on technique and endurance when I was younger. Three years ago I began to do specific hypertrophy and maximum power training. Currently I want to widen my skills and focus on training for bouldering. I analyse my competition and rock climbing performances and learn from them to prepare my training plan. Usually, at the beginning of the year I practice hypertrophy and maximum power training. In the early summer I go on with endurance training. During the international competition phase (often in the end of summer and fall) I do specific competition training such as on-sight climbing and try not to lose my level of endurance and maximum power. In the end of the year I usually go outdoors to do a lot of rock climbing. If necessary, I rest too.

Despite your young age, you have already shown a strong interest and even commitment to environmental and access issues related to climbing. What can you tell us about your experience and views about this topic?

David & Ruben: The first time we learned about the potential conflict between climbing and nature protection was when the German authorities decided to ban climbing in our home area, the Selter. They claimed that climbing wasn’t compatible with the growth of particular plants and life habits of animals. This felt like a paradox because climbing had been practiced there for over 100 years here and nothing has changed. No plant disappeared and the same species of animals that used to live there decades ago are still present. We think there was no big environmental impact triggered by the judicious climbers. There are already tried solutions such as seasonal bans of specific cliffs and areas, but the private interests of owners and their relationships with the local government seem to predominate.

The resolution they proposed required labelling of the rocks that we are still allowed to climb. But the authorities didn’t implement this labelling. This currently results in a complete ban for climbing, because it’s forbidden to climb on unlabelled rock. Thus another nonsensical situation has arisen. The legislation allows climbing on certain rocks, but there is still a total climbing ban because of the partial enforcement of the resolution.

Sadly the real problem behind this situation is due to the private interests of owners and their relationship with the government. In our opinion we are dealing with a growing erosion of social rights such as the freedom of accessing nature for purposes of recreation and sport activities. These rights are sometimes sacrificed for private interests. This follows the logic that success and achievement solely depend on the assertiveness of individuals over property and possessions. One of the consequences is the marketing nature as if nature was a private thing that can be owned by a few. Those having the upper hand in the Selter even proposed to lease out the rocks for money. In these scenarios, values such as participation, equal opportunities and conflict resolution lose importance. Apparently the Selter is a special case of this general development. We consider it a retrogression of social freedom to the advantage of privates.

The only alternative to this backwards development seems to be political action for now. Climbers in our region are demanding that climbing is adequately recognised as a valuable sport and therefore allowed in the Selter. For hard sport climbing in Lower Saxony, the area is exceptionally important and irreplaceable. It really hurts us young climbers because we cannot repeat fantastic and hard routes such as “1001 Nacht” (8c) or “Wipe out” (8c) anymore and we are not allowed to bolt anything new on great rock. Lack of local climbing also means that we have to travel several hundred kilometres south, mainly to Frankenjura, to find comparable climbing. This travelling is of course counterproductive in terms of pollution. So by short-sightedly fixing a non-existent problem with nature preservation, a real one has been created.

While travelling abroad we’ve talked with local climbers from other areas too about their environmental and access problems and possible solutions. In Catalonia for example they struggle with “open air toilet pollution” and poor behaviour from a minority of climbers. We often see that the paths are littered with trash too.

We think that the climbers should leave nature as they’ve found it. If everyone acted so, the impact would be very low. It shouldn’t really be so hard to have respect and compliance to the rules (often mentioned in the guidebooks or in the internet) on your way to the cliffs (park on the designated places, follow the paths and don’t cut through the vegetation), at the cliffs (take the trash with you, remove tick marks, don’t make a fire, don’t play music on your mobile phone or be inappropriately loud, don’t use too much chalk) and on your way back. Try to find political solutions (form communities of interests, be present on political meetings, build and maintain contact with politicians and owners). It is very helpful when the climbers make a contribution to a convenient atmosphere where problems can be constructively discussed. Everybody can benefit from it!

You can follow the Firnenburg brothers on their website and blog.

David is supported by Scarpa, Beal, Ready Climbing, Escaladrome, Athletic Sport Sponsoring and the DAV

Ruben is supported by Scarpa, Beal, Ready Climbing, SFU, Gearhead and the DAV

Return to the Rest Jug homepage by clicking here.

Liked this article? Let us know by liking our facebook page!

Or share it

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.